The Photographs

A few weeks ago a fellow photographic historian and blogger asked for help with the identification of two old photographs of comets, which his daughter had found in a scrap book in an antique shop in Delaware, Ohio.

The only clues he had were that they were albumen prints and that they were probably taken in the area of the 'Great Lakes', as they were accompanied by other photographs showing a lighthouse and lots of water. Leaves were also present on the trees, indicating the late spring-summer months of May to October as the likely seasonal date.

Now in any identification of old photographs, five questions have to be answered - Who, What, When, Where and How. In answering each of these questions often gives clues which help with the unanswered ones. I will begin with the easiest and leave the hardest ones until last.

Unknown Comet - Photograph No. 1

Unknown Comet - Photograph No. 2

How?

This is the easiest one to answer if the photograph is in your hands, thus enabling an identification of the photographic processes involved into taking the original negative and the production of the positive copy (if there is one).

In the case of the two cometary photographs, we know that the albumen prints. This fact narrows down the likely date for the photographs.

The albumen process was first invented in 1850 by Louis Désiré Blanquart-Evrard, and was the first commercially exploitable method of producing a photographic print on a paper base from a negative. It used the albumen found in egg whites to bind the photographic chemicals to the paper and became the dominant form of photographic positives from 1855 to the turn of the 20th century, with a peak in the 1860-90 period.

The negative is traditionally a glass negative obtained with a wet or dry collodion emulsion, but this step can be performed with almost any other photographic method, including gelatino-bromide 'dry' photographic plates.

From the above we can narrow the date of the photographs tbetween 1855 at the earliest to about 1910 at the very latest.

Who?

You might think that the answer to this question is obvious, that is it was taken by an astronomer. In fact it was almost certainly not the work of an astronomer, but a very good and experienced photographer.

The fact that, great has been taken in 'framing' the shots and especially the reflection of the comet on the water in the two photographs, is undoubtedly the work of either a 'jobbing' photographer or an amateur with a 'good eye'. An astronomer on the other hand always takes his cometary photographs at night against a starry background, not at twilight when these were probably taken.

Where?

The location of the photographs is almost certainly somewhere in the 'Great Lakes' area of North America.

They are a collection of freshwater lakes located in northeastern North America, on the Canada–United States border which connect to the Atlantic Ocean through the Saint Lawrence Seaway and the Great Lakes Waterway. The five lakes - Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie, and Ontario, form the largest group of freshwater lakes on the Earth and contain 21% of the world's surface fresh water.

A feature of the lakes is the presence of a number of impressive lighthouses, one of which was included in the scrap book.

Unknown Lighthouse

What?

This is a relatively easy question to answer in this case. The two photographs are of a 'Great Comet', by that is meant one that is visible in daylight.

A diffuse cometary image becomes noticeable to the naked eye when it reaches a magnitude of approximately 3.4 in a dark sky. Compared to a comet whose magnitude is 4, a 3rd magnitude comet would appear 2.5 times brighter and a magnitude 2 comet would appear 2.5 x 2.5 = 6.25 times brighter still, etc.

The brightest star in the sky (Sirius) has an apparent magnitude of about -1.4. At its brightest, the planet Jupiter appears at magnitude -2.7 and Venus at -4.4.

This fact narrows the number of possible comets down considerably.

In the years 1855 there are only nine possible candidates:

List of 'Great Comets' 1855-1910

When?

So which of the nine possibles is our mystery comet? The firm favourite has to be Comet 1882 R1 for a number of reasons.

It is the only one which is bright enough to be able to produce a reflection on water in twilight.

It was at its closest approach in the middle of September and therefore a 'summer' comet.

Also the tail was straight and long as shown by a photograph of the comet taken at about the same time (see below).

All the other candidath are either two faint, or reached perihelion in winter or had tails which were curved or in the case of 1861 J1 multiple.

So the likely mystery comet is therefore 1882 K1. QED!

Our comet photographs if they are of 1882 K1 then they are not only probably the two finest early images of a comet, but are alo extremely rare.

It is known that apart from the photograph depicted below, only David Gill, Her Majesty's astronomer at the Cape captured this comet on a photographic plate.

'Great Comet' 1882 K1 taken on the 28th of October 1882

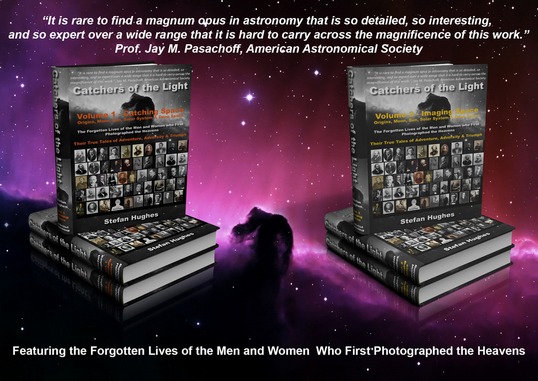

Buy the eBook or Printed Book at the 'Catchers of the Light' shop.