'The Showman & the Inventor'

Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre

Born: 18th November 1787, Cormeilles en Parisis, Val d’Oise, France

Died: 10th July 1851, Bry-sur-Marne, near Paris, France

Joseph Nicephore Niepce

Born: 7th March 1765, Chalon sur Saône, Saone-et-Loire, Bourgogne France

Died: 5th July 1833, Saint-Loup-de-Varennes, Saône-et-Loire, France

On the 7th of January 1839, members of the French Academie des Sciences were shown images that would provide Astronomy with the means to unlock the very secrets of creation. What they saw was the work of a Parisian showman, named Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre, who had relied heavily on the earlier efforts of his now dead partner, the inventor, Joseph Nicephore Niepce. In 1839 Daguerre attempted to photograph the Moon and failed. Astrophotography was about to be born.

The astonishingly precise pictures they saw were the work of Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre - a Romantic painter and printmaker; most famous until then as the proprietor of the Diorama, a popular Parisian spectacle featuring theatrical painting and lighting effects. Each Daguerreotype (as Daguerre dubbed his invention) was a one of a kind image on a highly polished, silver-plated sheet of copper. It was the Polaroid of the day.

Louis Jacque Mande Daguerre (1787-1851) made no significant contributions to Astrophotography with the exception of his failed attempt to produce the first photograph of the Moon; which unfortunately has not survived.

“La préparation sur laquelle M. Daguerre opère, est un réactif beaucoup plus sensible à l’action de la lumière que tous ceux dont on s’était servi jusqu’ici. Jamais les rayons de la lune, nous ne disons pas à l’état naturel, mais condensés au foyer de la plus grande lentille, au foyer du plus large miroir réfléchissant, n’avaient produit d’effet physique perceptible. Les lames de plaqué préparés par M. Daguerre, blanchissent au contraire tel point sous l’action de ces mêmes rayons et des opérations qui lui succèdent, qu’il est permis d’espérer qu’on pourra faire des cartes photographiques de notre satellite.”

“The process of M. Daguerre is much more sensitive to the action of light than those which had been used so far. Never before has natural moonlight produced any perceptible physical effect, even when magnified with the largest lens, or focused by the biggest reflective mirror. The plates prepared by Mr. Daguerre, bleach on the contrary the surface under the action of these same rays and it is hoped when he is successful with his experiments, one will be able to make photographic charts of our satellite.”

Francois Arago 1839, Perpetual Secretary, French Academie des Sciences.

However, as one of the great pioneers of early Photography, and without doubt its finest publicist, it was felt only right that the first 'Catcher' blog should be devoted to him. A more important reason for his inclusion is that the very first astronomical photographs taken during the 1840s were Daguerreotypes and not the Calotypes of his arch Nemesis – William Henry Fox Talbot.

The name Joseph Nicephore Niépce is unknown today by all, with the exception of a few photographic aficionados. Yet it was Nicephore Niépce who took the first true Photograph some thirteen years before Arago made his historic announcement to the world, extolling the images of Louis Daguerre. However in recent years there have been efforts by Photographic Historians to redress the balance in Niépce’s favour.

How did it come about that the name of Daguerre is engraved so deeply in the pages of history, and that of Niépce has been so effectively erased from it? We will now tell the story of how this distortion of history came about: and it is only right that it should be done:

“It is the first and fundamental law of history that it should neither dare to say anything that is false, nor fear to say anything that is true, nor give any just suspicion either of favour or disaffection; that, in the relation of things, the Writer should observe the order of time, and add also the description of places ; that in all great and memorable transactions he should first explain the counsels, then the acts, lastly the events; that in the counsels he should interpose his own judgment on the merit of them; in the acts he should relate not only what was done, but how it was done ; in the events he should show what sheer chance, or rashness, or prudence had in them ; that in regard to persons he should describe not only their particular actions, but the lives and characters of all those who bear an eminent part in the story.”

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106 BC – 43 BC), Roman Philosopher, Orator and Statesman.

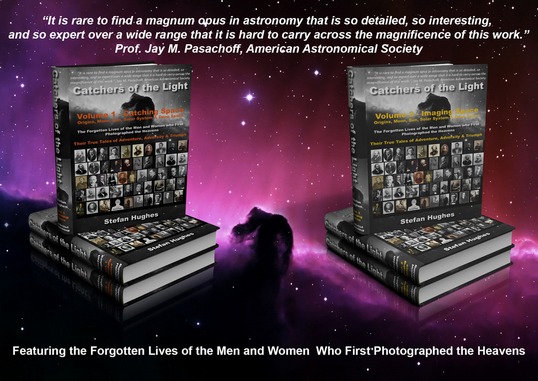

To read more on their life and work read the eBook chapter on Louis Daguerre & Nicephore Niepce or buy the Book 'Catchers of the Light'.

Daguerreotype by Louis Daguerre, Boulevard du Temple, Paris, 1839

Buy the eBook or Printed Book at the 'Catchers of the Light' shop.