'The Elemental Man'

Born: 22nd February 1824, Paris, France

Died: 23rd December 1907, Meudon, France

Pierre Jules Cesar Janssen used photography to study the Sun and was therefore one of the founders of Solar Physics. In 1868, during an expedition to India to witness a Total Eclipse of the Sun, Janssen noticed the presence of an unknown line in the yellow part of the solar spectrum at a wavelength of 587.4 nm; which was later found to be produced by a new and as yet undiscovered element – now known as Helium. This was the first chemical element to be discovered on another world.

In an episode of the well known American cartoon series, the Simpsons, Principal Skinner, the head of Springfield School is seen to raise his fist and utter the words: “Curse the man who invented helium! Curse Pierre Jules César Janssen!”.

In 1868, over a hundred and thirty years earlier, the French scientist and astronomer, Pierre Jules Cesar Janssen (1824-1907) had travelled to India to witness a Total Eclipse of the Sun, which was due to take place on the 18th of August that year. During the expedition he noticed the presence of an unknown line in the yellow part of the solar spectrum having a wavelength of 587.4 nm, which was totally unfamiliar to him:

“The bright yellow line was actually located very close to D [sodium], but it belonged to refrangible rays more than D. My subsequent studies on the Sun show the accuracy of what I say here.”

However, the line was also noticed on the 20th October 1868 by the eminent English scientist, Sir Joseph Norman Lockyer (1836-1920) who in 1870 concluded that this was due to an unknown chemical element, which was later to become known as helium after the Greek God of the Sun – Helios.

This was a momentous observation as it led to discovery of the very first chemical element to be found on another world. Although, Janssen’s observation of the chemical element Helium made him famous, it was not the only significant contribution he made to science.

In 1862 Janssen had established an observatory in the Montmartre district of Paris, where he carried out investigations into the Solar Spectrum. He believed that some of the dark absorption lines in its spectrum did not emanate from the Sun itself, but were caused by the earth’s atmosphere. These became known as the Telluric Lines, a name given to them by Janssen.

On the 19th of August 1868, a day after the total eclipse, Janssen made a discovery which had a major impact on Solar Physics. He found a method of utilizing the Fraunhofer ‘C’ Emission Line, also known as ‘Hydrogen Alpha’ by which he could observe the spectra of Solar Prominences without the need for a Total Solar Eclipse. The same method was independently discovered somewhat later by his friend, Lockyer. The French Academy of Sciences struck a medal bearing the effigies of the two scientists to commemorate the achievement. A ‘Hydrogen Alpha’ filter is still used today by the modern day Astrophotographer to obtain images of the Sun’s surface, its prominences and flares. For this we have to thank Janssen and Lockyer.

In 1874 Janssen went to Japan to observe the transit of Venus, and in order to witness the exact moment of the planet’s contact with the sun’s limb, he had developed a special camera he called the ‘Revolver Photographique’. This remarkable instrument was able to take a rapid series of photographs with very short exposures showing Venus’s approach towards the limb of the sun. It was the very first webcam!

However, it was his ‘L’Atlas de Photographies Solaires’, published in 1904, which earned Jules Pierre Cesar Janssen his right to be called one of the great pioneers of Astrophotography and one of the founders of modern Solar Physics. This remarkable work contains some 6,000 photographs of the Sun taken in the years 1876 to 1903 from the newly established Meudon Observatory, near Paris; which was later to be known as the Paris Astrophysical Observatory.

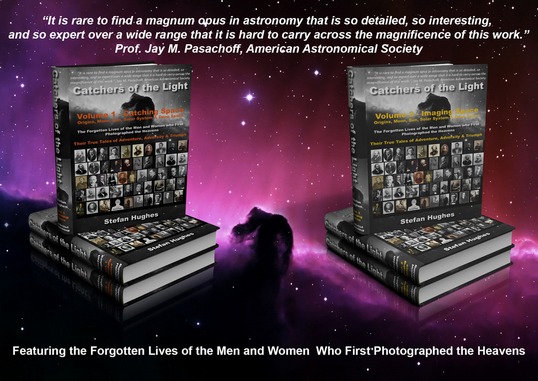

To read more on his life and work read the eBook chapter on Pierre Jules Cesar Janssen or buy the Book 'Catchers of the Light'.

The Solar Surface, from L'Atlas Photographiques Solaires, Jules Janssen

Buy the eBook or Printed Book at the 'Catchers of the Light' shop.